“Kuna twiga pale,” I say in Swahili to our driver Meshak. There are giraffes over there. My partner Dr. Derek Lee and I stand side-by-side in the back of our Land Cruiser, its top opened, and peer through our binoculars at a herd of Masai giraffes (Giraffa camelopardalis tippelskirchi) feeding on umbrella-shaped Acacia tortillis trees several hundred meters away. We are deep in the heart of Tarangire National Park in northern Tanzania, East Africa. “I see at least 12 giraffes,” Derek says. “Let’s head over there.” As our vehicle bumps across the savanna towards the herd, some individuals continue eating and milling around, while some lift their heads and watch our approach, serenely chewing their wads of cud. As long as we advance slowly and do not drive directly towards them, they are unconcerned.

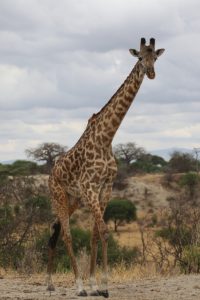

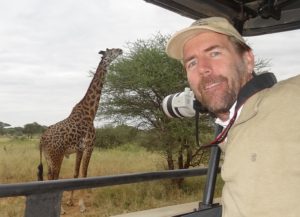

We carefully scan the ground for aardvark holes and logs hidden in the grass as we proceed forward. The closer we get to the giraffes, it strikes me how absurdly tall and oddly shaped, yet wonderfully elegant these majestic creatures are, the world’s tallest of animals. When we are about 70 meters from the closest giraffe, we swing the vehicle around to see her right side. Derek photographs her while I measure her exact distance away from the camera using a laser rangefinder, so later we can use photogrammetry to calculate her height. I record the photograph number, her distance from camera, and her sex and age class in our field notebook. Moving on to the other giraffes, we weave in and out of the trees and bushes, constantly adjusting our angle to get photos perpendicular to the animal. If we witness a nursing calf, we make a note connecting the cow-calf pair. We also record anything unusual such as signs of disease or injury. After everyone has been photographed, we mark a GPS location in the approximate center of the group, make a final count of all the giraffes, and follow our original tracks back to the road. As we drive off, the giraffes stare after us with their big, long-lashed eyes, chewing intermittently, but otherwise completely unfazed as we depart with more data points in our growing set of thousands of photographic giraffe ‘captures.’

Derek and I are implementing the world’s largest individual-based demographic study of giraffes in terms of sample size and area sampled. We conduct six surveys per year towards the end of each of Tanzania’s three precipitation seasons, with every survey lasting about 10 days. We are investigating births, deaths and movements of giraffes in the Tarangire ecosystem—a region undergoing rapid anthropogenic land-use changes—to understand where they are doing well and why, and using that information to conserve declining giraffe populations. For my PhD in the Program Ecology at the University of Zürich, I will be using our photographic capture-recapture data to study giraffe natal dispersal patterns and to quantify the fitness consequences of their social dynamics. I am part of both the ‘Population Ecology’ and the ‘Cooperation and Social Structuring in Mammals’ research groups.

Despite being an African icon and one of the planet’s last mega-herbivore species, giraffes remain understudied in the wild. In part, this is because giraffes were not intensively hunted until recently in some areas: they don’t produce tusks or horns that are coveted as trophies or medicine and they are not an aggressive species. Sadly, however, giraffes are becoming increasingly endangered throughout their range in sub-Saharan Africa due to conversion of savanna woodland habitat to agriculture, deforestation for charcoal, and bushmeat poaching.

Giraffe numbers have plummeted across Africa by an estimated 40 percent in the last few decades, to the point where they now number far fewer than African elephants. The IUCN recently upgraded the species Giraffa camelopardis to “vulnerable” on the Red List (while scientists are debating the number of species, all giraffes are currently still considered to be one species). Most giraffe populations are now largely restricted to lands in and around national parks. Predation by lions and hyenas also can negatively affect giraffe survival—a natural phenomenon that becomes a problem as wildlife are squeezed into small protected areas.

After decades of little research on the wild giraffes, scientists are showing renewed interest in these gentle giants because of their declining numbers. Derek and I began photographing individual giraffes in 2011 to build a database of demographic information on giraffes across the Tarangire ecosystem. This region, which contains two national parks and a large private ranch embedded within a matrix of village lands, is known for its extraordinary diversity and abundance of large mammals including giraffes, elephants, zebras, antelopes, lions, and leopards, but these magnificent animals exist in a landscape undergoing rapid changes.

The Tarangire ecosystem is second in giraffe density only to the nearby world-famous Serengeti ecosystem, but unlike the Serengeti, land in Tarangire is largely unprotected. Since the 1940s, human population and agricultural expansion in Tarangire have increased fivefold, causing substantial habitat loss and fragmentation. Bushmeat poaching is also a serious problem—recent research suggests that each year poachers kill about 90 giraffes in just one small part of the Tarangire ecosystem. Giraffes are hunted at night, dazed by spotlights or confused by loud horns and killed with machetes or spears; giraffes are also targeted with wire neck snares set high in the tree canopy.

We study wild giraffes using two technologies, digital photography and pattern-recognition software, to identify and track individuals by their coat patterns. Every giraffe has unique and unchanging spot patterns, much like the human fingerprint. These patterns enable us to identify and monitor individual giraffes with the aid of a computer algorithm that matches the thousands of photographs we collect during our surveys. We can determine where and when we last saw the animal, whether a female was pregnant or nursing, and who else was in the herd. Demographic studies of uniquely patterned species using the non-invasive photographic method have grown in popularity as digital cameras and pattern-recognition software have improved. These technologies allow us to compile demographic data on thousands of giraffes—sample sizes unheard of in the days before computers. The method is also much less expensive than physical captures for marking of large mammals, and is entirely non-invasive and non-traumatic. Other recent demographic studies using pattern-recognition software with digital photographs have been conducted on wild dogs, wildebeests, and even toads (my UZH colleagues Sam Cruickshanck and Benedict Schmidt just published a study on yellow-bellied toads in Switzerland using the same pattern-recognition software that we use).

To date we have identified and are monitoring over 3,100 individual giraffes. We aim to understand factors affecting survival and reproduction in landscapes subjected to different human uses, including parks and village lands, and also to identify important calving grounds and critical movement pathways. My PhD research will help ascertain how human and natural factors influence sociality and fitness, and how these mega-herbivores move around the ecosystem, which will provide insights into what may be the most effective conservation measures. The ultimate goal is to enable healthy populations of giraffes to continue roaming across this ecosystem as they have for eons, fulfilling their important ecological functions and delighting humans for generations to come. The Masai Giraffe Conservation Demography Project is being conducted by the Wild Nature Institute. Visit their website to learn more.